This podcast is brought to you by the Center for Services Leadership, a groundbreaking research center in the W.P Carey School of Business at Arizona State University. The Center for Services Leadership provides leading edge research and education in the science of service.

——————————

Darima Fotheringham: Welcome to the CSL Podcast. I am Darima Fotheringham. Today I’m talking to Scott Broetzmann and Mary Murcott. Scott Broetzmann is the Co-Founder, President and CEO of Customer Care Management & Consulting (CCMC) and Mary Murcott is the President of the Customer Experience Institute for Dialog Direct. They will share insights from the latest Customer Rage study that CCMC and Dialog Direct conducted and partnership with W.P Carey Center for Service Leadership. Scott, Mary, thank you both for being here today!

Scott Broetzmann: Thank you.

Mary Murcott: Thanks for having us.

Darima Fotheringham: This is the 7th wave of National Customer Rage study. When and how the Customer Rage study begin?

Scott Broetzmann: The concept of the National Customer Rage study goes all the way back to 2002, but it really wasn’t about customer rage at the time. It was much more narrowly conceived as a replication of a very famous study, a notable White House study from the mid-70s that my colleagues, John Goodman and Mark Grainer, did for the White House. It was that seminal piece of work that connected the words “quality” and “profit”. And the study had not been updated in close to 30 years. When we founded CCMC, one of the things we wanted to do was to provide really good actionable information in the marketplace about the customer experience. So we said, why don’t we redo the “White House study”?

Along the way, when we were first conceiving the study, we thought that we ought to put in some new things as well. One of the things that I read in The Washington Post was an interesting article about how local retailers here in the Washington D.C. area were having trouble holding on to their retail staff because customers were so angry and awful to them, and the pay was so low. It struck a chord with me. I did a literature search, looked around and there were all kinds of anonyms or acronyms for rage that were out there. There was software syndrome rage, road rage, and restaurant rage but there wasn’t really any empirical research, anything meaningful that was even quasi scientific with the exception of one study that, I think, was at the University of Buffalo that talked about angry customers.

It left me feeling that people were saying angry customers and customer rage was really the stuff of lunacy. It was a hyperbole, it was an exception. It was just crazy people that painted the car yellow and stood outside the auto companies, lemon laws, that sort of thing. And that didn’t seem right to me. I knew personally, I’ve gone through my own fits of rage from time to time with products or services. Long story short, we added a question or two on rage. The rest as they say is history because the first Rage Study that came out was published in The Wall Street Journal. It continues to enjoy coverage in the popular press and in a lot of other places.

I would also make these other two side notes. First, I think part of the reason that so many are attracted to the Rage Study, outside of some of our friends in the corporate world that manage customer care, is that everybody has their own personal story of rage. A lot of the times, when we present the Rage Study, everybody comes with their own passionate stories about their worst product and service experiences. Everybody gets really jazzed up before we even start talking about data. A part of the reason why the Rage Study is connected is tied to that.

And I would say as well, it’s the only longitudinal study that offers credible trustworthy data about complaining experience. There’s lots of other studies out there, like American Customer Satisfaction Index, J.D. Power, etc. But this is the only study that, over the course of now in effect of a decade, provides a credible view of what it’s like to deal with a company when you have a problem. That’s really an important part of the Rage Study story.

Darima Fotheringham: Right. And looking at the data collected over the years, what can you say about the most common triggers of customer rage, let’s say ten-fifteen years ago and now? Have they changed?

Mary Murcott: Good question. About 10 or 15 years ago we led simpler lives. The cable companies were not in telephone service, were not in security, were not in wireless service. As we start bundling services in the banks and in telecommunications, we’ve seen the complexities rise. Not only has the complexity risen because we have bundled services, but companies that have actually listened to the customers, added a lot of features and a lot of channels in which they can communicate. That’s causing a lot of customer bouncing from one representative to another representative. So I think the common trigger is complexity.

The features have gotten complicated, so customers have more reasons to call because it’s not intuitive how to use a product or service. Secondly, they don’t know who to call within the company and, lastly, the company isn’t really sure if the representatives have been clearly trained or they lack a common database about customers, a common database about knowledge. That’s become a real problem. So, I think, it’s complexity that is driving the rage at this point.

Darima Fotheringham: Going into the latest customer rage study, did you have any predictions about what you’d find? Were the predictions confirmed? Were there any surprises?

Scott Broetzmann: So what’s interesting of sort, turning a lemon into lemonade, is that the rage data, over the course of these seven times we’ve done it, hasn’t really moved very much. Sometimes, the key indicators are sort of static or now we’re starting to see, now that we have a longer term view – that’s why the longitudinal view is so important – things can move just a little bit, but over the course of seven times over 13 years or so, every little bit adds up to a lot. So there’s a slower decline, maybe, but things are in decline for some of these really important measures.

We keep waiting for some sort of sea change, some kind of positive tracking in these KPIs but we haven’t seen any. In the first few years of the study, I’d say we were surprised by the order of magnitude of unhappiness or discontent with complain handling. We knew from our proprietary work that we’ve done for many decades that it’s probably fair to say about many companies that complaint handling isn’t their core competency. We knew that to be true. I think what we were surprised at initially was just how many companies were so bad at complaint handling, and that continues to be the case today. But as far as predictions, like Linus and Lucy waiting in the pumpkin patch, we keep going every year, every other year. We do the Rage Study, hoping to see the Great Pumpkin here has changed in some of these key indicators, but every year we’re walking back at the end of the night with our blanket in our hand and nothing’s really happened.

I will say that has created a certain imperative for us to continue to explore the “why” and the “how” of rage. This time one of the things we did – and we do a little bit something different every time we do the study to delve deeper – we looked at the most annoying phrases that are part of the Customer Care lexicon. We had folks rate fifteen different common phrases that they would often hear when they’re trying to get their problem solved. I think these phrases, to some degree, when you reflect on them, have a lot to do with why somebody might say, “I didn’t really get anything”, or they might encourage people to be a little bit more enraged or they might create the feeling that “the company really isn’t putting itself in my shoes”, which is one of the things that people often want.

The top five of these annoying phrases things which many people thought should be “banned” from customer care conversations:

- Number 1: “Your call is important to us please continue to hold.”

- Number 2: “That’s our policy.”

- Number 3: “We’re currently assisting other customers, your call be answered in the order in which it was received.”

- Number 4: “Can I get your account information again?” – How many times have we heard that and just wanted to take the phone and throw it through the wall because you just spent 10 minutes entering in all of the information that they’re going to ask for again?

- And number 5: “Please give me top scores and all the questions in the after-call survey”, begging for positive reviews.

Those are palpable annoyances for customers and they are big contributors to the lousy experience that we’ve, at least by the rage study, so often seen happening. I don’t know if there’s again any great “news” to those, as much as there is maybe a disappointment that in this day and age, when customer care really become so pivotal, and so much has been invested, we’re still having these kinds of conversations about what could be improved.

Mary Murcott: Darima, I think from my point of view, I only had one surprise. I would hope to have been surprised by some positive changes, I wasn’t. But one surprise I had – and, I guess, looking back and reflecting on it, I shouldn’t be surprised – was that the amount of rage really increased. And I look at one statistic in particular, the number of customers saying “They wanted revenge on the company” increased from 3% to 24% in two years. That surprised me, but it shouldn’t have. I think, when we look at politics and the overall community – and I mean the general consumer community, about how they’re being governed, how they’re being managed, how their large corporations have trained them – they’re really starting to revolt. I think that’s what we saw about the revenge going from 3% to 24% in two years. So it’s disturbing but I think it’s understandable.

Darima Fotheringham: Were there any other interesting trends and statistics?

Scott Broetzmann: I would add two additional statistical trends that stick out. One, and this relates to channel, 72% – and that’s the percentage of respondents that cite to have had a problem complaint – cite the telephone as their primary channel for complaining, which is more than a six-to-one margin versus the Internet. And, I think, you’re on firm ground, as in our business, telling organizations that they really need to be vested in a multi-channel approach, they need to optimize all the new kinds of digital ways of communicating. Those are all really important. That’s not the argument being made here. However, when somebody has a problem, their go-to-channel is the telephone. I think that’s a surprise to people, if you want to go back to surprises, and I think it’s also a warning to companies that you can’t forget about that channel for these problem-handling scenarios. To Mary’s point about complexity problem of products and services, sorting some of these things out is not easy, and it isn’t going to be resolved in a 142 character tweet. You have to actually talk to people in order to resolve some of these problems. That’s one.

Second one is that in 1976 the percentage of households that were satisfied with the way a company responded to their question or problem was 23%. So almost a quarter, one in every four customers in response to their most serious problem was going to be satisfied. Here we are in 2016 now, the study was done in 2015, and it is only 17%. How is it possible that over four decades of work advancement that we’ve actually lost grounds? That still is a phrase that we repeat often in 13 or so years that we’ve done the Rage Study but it’s the one that merits repeating and merits attention. If that trend were to continue, I guess by the time, well I would be retired, I don’t know about Mary, that trend will bring that number down into the single digit. So that’s what we hope doesn’t happen.

Darima Fotheringham: So it seems that many companies are still struggling to provide great customer care, but do you think customers are becoming more demanding these days? What can we learn about the customers from this study?

Scott Broetzmann: Great question! There’s a couple of ways to think about them. The first question “Are customers more demanding?” many companies believe this to be true. One of the more common reactions that I would hear to Rage Study, particularly in the earlier years, is that, “Well, we’re doing plenty, but you can’t please everybody and especially today’s customers, who are overly demanding and unreasonable.” And I don’t buy that premise, when I look at the rage data.

First, to Mary’s point earlier, problem experience is up. In 1976, the percentage of households with a problem was 32% and in 2015 it’s 54%. That’s a big increase. And that’s despite tremendous increases in the quality of products and services. You could take automotive for instance, quality there is really, really improved. But in this global, digital, outsourced, co-branded, make-incremental-revenue model type marketplace, I think it’s entirely fair to say that complaint handling is even more important than it ever has been. It has more impact because of this increased problem experience that there’s ever been before.

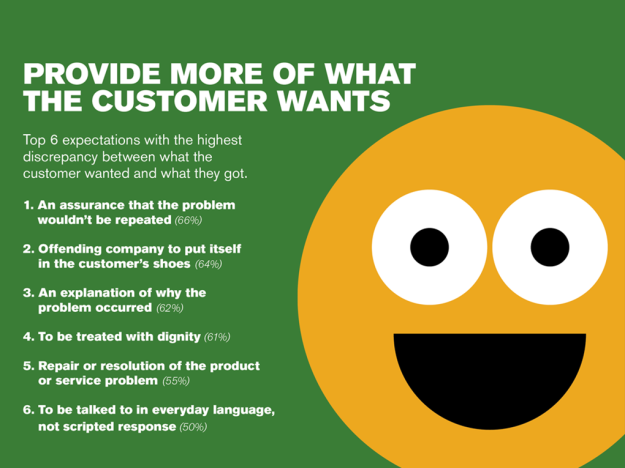

Secondly, to this issue of whether customers are more demanding, oftentimes the corporate response will be “Well, they want reasonable things. We can’t give them what they want. They want money, and they want free products, and they want to cheat us.” Significant efforts are made to detect and find the one person out of a thousand that’s completely dishonest and unreasonable, while at the other end of the continuum are a bunch of customers that want things that don’t cost anything. Most of the things that customers want, we find in the Rage Study, have no cost. And they are things that you would imagine would be provided. The number one thing that they want is to be treated with dignity. But number two thing that they want is for a company to put itself in the customers’ shoes. We can go down that list. I think seven of the first eight are things that have nothing to do with money. They have to do with the simple non-monetary remedies.

Companies, many aren’t set up to talk to customers, and we said that the channel a preference for complaints is telephone. But whenever I call a contact center now, I dread it. Trying to sort out some sort of serious problem, it’s awful when you have to go through this entire daisy chain that starts with the automated telephone and then continues with agents that might say something like, “Hello, who I have the pleasure of speaking with?” All of the annoying phrases that we’ve talked about become part of a conversation. That’s not a dialogue. That’s not a conversation. So when you look at: are they more demanding? I don’t think they are demanding. I just think that companies, to some degree, when they don’t get this right, have divorced themselves from what the reality of the genuine conversation is.

Mary Murcott: You know, Scott, I agree with you on so many of your points. I don’t know if customers are more demanding. I think they’re certainly more discerning. They are certainly making comparisons with other industries saying: “Hey, if USAA can do it, why can’t you?” Even if you’re not in the insurance industry. I also agree with Scott that a lot of companies are creating policies and procedures, audit and legal are creating things around the few dishonest people, either employees or customers. I have worked for companies that I really admire, and American Express is one of them. One of the things they taught me, and one of the values they have is assume positive intent. You build policies which match the vast majority of people and you audit for the other thing. And I think that somehow both legal and finance have taken over a lot of companies in the game toward looking toward the bottom line. And I see that when I look at complexity. When I look at the companies and industries that aren’t doing well, it’s about the three C’s. I talked about Complexity and there are two other things as well. That’s Compliance and Change, also driven by those legal people saying you can’t apologize.

The complexity drives the amount of change and the compliance is driving a scripted response. I see so many scripted responses. Sometimes you have to do it because legal or the big government has told you, you have to say it exactly that way, so that the customer is not getting scammed. And then, what I see is the entire conversation becomes scripted. When people call a call center, what they are really looking for is a relationship. They are looking for empathy. They’re looking for something only a true person can give them. And when we come back with a scripted response, it’s a real problem.

Other thing that customers really want is they want a true and sincere apology. Not “We’re sorry”, but an “I’m sorry”. We need to train empathy. When I look at the best companies out there that do this, they stopped training so much on policies and procedures. They will train how to look up the policies and procedures. But they train more on relationship management skill. That’s why people, who use the phone, crave a relationship with these company, so that exceptions can be made, that people really listen to their side of the story. That’s really hard to do in an email or online chat. You can’t have a relationship over a computer. You need to hear the empathy and the sincere apology that’s behind that company.

So what’s interesting to me is that 50% of companies that I talked to – and I actually did an informal survey the other day, and that was 56% of companies – will not let their employees apologize. Why? It’s because of assumed liability. And what we found is when a sincere apology is offered, there’s less likelihood of being sued. So again, who’s really running these companies? People that care about customers and a marketing department? Or is that legal and finance that are doing it, to their own detriment by the way?

Darima Fotheringham: That’s great insight. Thank you, Mary. What else can companies take away from the customer rage study? Is there anything we haven’t discussed?

Mary Murcott: I think we need to make it easier to complain. One of the big concerns, if you think about it, is that even if a customer is completely satisfied with a complaint handling process, 52% of them still will not recommend your company. We need to make it easier for customers to complain so that you are consciously knowing what’s happening to your company. Because if you don’t make it easy for them to complain, and they have this thing that my good friend John Goodman calls “trained helplessness”, they stop complaining because they get nothing for complaining. They go away and they go to your competitor, and you don’t even know that you have a problem with your company or with that customer. They just go away. Making it easier to complain and then actually doing something about it will not only address the complaint but also the root cause of the problem. We need to make it easier for people to do business with our company. So you’ve got not only make it easier to get more complaints in the door but, secondly, you have to fix that problem on the first call and give them what they really want. Then, lastly, do some root cause analysis to eliminate the root problem because even if you satisfy the complaining customer, they’re not going to recommend you 52% of the time.

Scott Broetzmann: I’m going to suggest that too many companies live in a state of blissful ignorance about the quality of the service that they’re providing. That’s often because they have such tepid ineffectual metrics by which they assess the quality of their service. Their metrics are insincere. No one, no company, if they looked at the Customer Rage results or looked at their own company results for this sort of activity, would accept the levels of performance that you see. No one that’s still working, because they wouldn’t have a job. And so you have to believe that while intentions may be good, oftentimes, to Mary’s point, people that are making decisions – let’s just say these contact centers that we’ve been referring to, if we were going to concentrate on the telephone – don’t have the right information to really understand what the quality of service is. And, when you think about it, in contact centers today, at least by my experience, a lot of these sorts of measures are tending towards validating that things are OK.

For example, the use of quality assurance metrics. I have yet to walk into a contact center where quality assurance statistics didn’t suggest that 90% to 98% of the compliance requirements have been met, which is translated into: These were really good calls. And when you think about it, some of the things that are being monitored, some of them legal to Mary’s point, some of them marketing related – I mean these requirements that you say a customer’s name twice or three times – are completely meaningless from a customer satisfaction standpoint, absolutely no relevance at all to the kinds of KPIs we’ve been talking about, like getting what you want and satisfaction with the call, feeling as if you’ve got something. But yes, those are featured criteria in many call quality evaluations or IVR surveys, which now are really, really prevalent.

It’s hard to make a call and not have the automatic invite, sometimes administered via the automated telephone, sometimes via the rep. And then you take the survey and it’s three or four questions. Well, one of the most important things that can happen in many contacts centers, particularly if you have a problem, is follow through. You have to fix the bill, you have to send something out, you have to call a retailer. There’re all kinds of different follow ups that are required. Well, an IVR survey doesn’t measure that at all. Much like the old days in the airlines sorts of measurement, where they would measure the things they tended to before you got off the plane, and it didn’t include anything on baggage. But what was one of the most frustrating part of flying, then and now? The baggage experience. So a lot of the strategic emphasis should be placed on better self-awareness, better corporate self-awareness, which, in my mind, has a lot to do with using more metrics with teeth of the variety that appear in the Rage Study.

Darima Fotheringham: Great. Mary, do you have anything to add?

Mary Murcott: What I would say is the companies need to listen to the Rage Study and then translate it into action. I talked to so many new MBAs that are put in charge of the call centers put in charge of customer satisfaction or customer experience officers who will look at the study, and they don’t really know what to do with it. For me it’s loud and clear. There are probably ten or fifteen things that they want banned from the call centers’ culture or multi-channel culture in terms of practices that annoy customers.

Secondly, there is a framework, in my opinion, in the Rage Study for building a true service recovery program that really delivers long-term loyalty. What we have from the customer are 12 things that they want in order of magnitude. We know that they are both monetary and non-monetary. We know customers want to be treated with dignity, which means they want to be heard and really listened to, not interrupted with “I know what the problem is and I can fix the problem for you.” They want you to hear their whole story. They want an apology. I think that the Customer Rage study gives a framework and actual action items that we can go do to change things. But what I hear from most executives and especially people right out of grad school is they don’t know what to do with the data. They say it’s interesting but it stops there and it really shouldn’t. It is such a great framework for change in action. So I think that moving the study from interesting into action is where we need to go next.

Darima Fotheringham: Right. What would you like to see in the results of the next wave of the customer rage study? Will there be another one?

Scott Broetzmann: Well, there should be another study. I noted earlier that, perhaps, the thing we’re most proud of is that it offers a longitudinal view. I know we’re all committed to seeing through more Rage Studies. To Mary’s point, I would second it and third it and fourth it, that we’re unlikely to see big changes in some of these numbers that we hoped we would, until some of the fundamental transformational changes in strategy are made at a more national or global level, whether it’s some of the things that are related to outsourcing or how you train or the kind of metrics you use. But we’ll keep trying. We’ll leave the light on, we’ll be around.

Mary Murcott: I would like to see a companion study to the next Rage Study. The one that takes a look at those who have vastly improved their scores and their industries. There are other studies where we can see huge changes year over year in complaint handling and improvement in customer satisfaction that translates into loyalty. I’d love to see correlation studies with them, where we ask companies that have actually moved the numbers: What did they do? And see if it correlates with the Rage Study, I bet it does. I think that’s more proof to companies that they need to get on with it and use the Rage Study as a framework for action.

Scott Broetzmann: I’ll leave my remarks with this one additional point building on Mary’s hope for the companion study. The study I’ve always wanted to do alongside the Customer Rage study is the employee front-line service version of Rage Study. A study, where we are able to get insights from those we rely on to help us about the types of experiences they have with customers, and find out what their suggestions would be for how to get more bees with honey, what their ideas would be about how customers can conduct themselves differently in order to make for a better relationship and a better service experience. Because, truth be told, if the higher order of aspiration here is to conduct business in the context of a relationship, well, you have to have two to make a relationship, at least. It goes both ways. And we’ve never been able to find a company that would be willing to let us have access to their front-line service folks to ask some of these really important and telling kinds of questions. We tried a number of times, but I’m still hopeful, as Mary is, that maybe we’ll be able to do some of these creative things.

Darima Fotheringham: In conclusion and, I know, you’ve given really great advice to companies. Is there another advice you would like to add? What one advice can you give companies to get us there, to get us where we want to be in terms of customer satisfaction and relationship building between the companies and customers and front-line employees?

Mary Murcott: I think the one thing that I have not mentioned that I wanted to was a common knowledge management database across channels and across departments. So many times customers get flip-flopped because things are changing so much – I mentioned that change is one of the three Cs – but there’s no common knowledge database that is, not Google style, but is more context related in terms of what customers really want and that drives to a good answer. When we ask customers in our own study, proprietary study by Dialog Direct, what the customers really want, the number one thing that they want is a knowledgeable person. I think they want knowledgeable channels too. So if they’re on the Internet and they’re looking at it, they’re getting the same answer.

Knowledge management systems that I’ve seen out there are pretty archaic. We found a good one at Dialog Direct that we use. And we have seen huge changes in customer satisfaction and in what we call in the industry first contact resolution statistics, where we actually are solving customer’s problems on the first call. And that’s another thing we hear that customers want out of a person. Now, they want good relationship and they want knowledgeable and friendly but, because time is money to them, – and that’s one of the big things that comes out of the study, they are equating time with money – don’t waste their time with someone who isn’t really knowledgeable. And that knowledge comes from a good system that backs up customer care.

Darima Fotheringham: Scott?

Scott Broetzmann: Mary said it all. She has the last word.

Darima Fotheringham: Mary, Scott, thank you so much for talking to us today.

Mary Murcott: Thank you

Scott Broetzmann: Thank you so much for making us a part of it.

Outro: For more information on the science of service, this is Center for Services Leadership on the web at wpcarey.asu.edu/csl.